Infinite Stabilisers, Protecting us from Chaos

How Final Destination captures modern death anxiety

The slasher film franchises of the 2000s get a bad rap. Wedged between the slasher classics of the 80s and the trauma-focused ‘elevated horror’ of the 2010s, 2000s slashers are often written off as mindless entertainment, or worse, crude, exploitative ‘torture-porn’. But this dismissal is reductive — beneath their trashy exterior, the greatest 2000s slashers strip away subtlety and pretention to gnaw on the existential roots of horror.

To my mind, no franchise confronts these base fears as directly as Final Destination.

The Final Destination (FD)1 films stick to a rigid formula, making an elevator pitch easy: Protagonist and ensemble are in a vehicle — plane, truck, rollercoaster, any unwieldy automotive really — when the protagonist has a vivid premonition of their spectacularly violent fate, and saves the ensemble’s lives. Slowly, the survivors begin to perish in inexplicable accidents following the exact order they would have died. The protagonist realises they have foiled Death’s grand design, and that Death is finishing what it started.

In FD, Death is a gleefully creative force of nature, not quite omnipotent but ultimately inescapable. There are many, many automotive accidents, smatterings of stove-fires, botched surgeries, swimming pool drownings — Death takes the form of the props that make up the modern world, their fatal malfunctioning.

The original Final Destination (2000) is the most successful in sustaining a palpable sense of dread. The environments feel tactile and flimsy, poised to collapse/derail/implode at any moment. Devon Sawa is striking as the dishevelled lead Alex. Alex has the initial premonition but afterwards is relegated to a sweaty exposition spewer, doomed to figure out Death’s design moments too late — but Sawa sells this character fully, you really feel his existential desperation in a manner no sequel protagonist comes close to.

But there is something else. FD’s pulpy premise hints at a deep-seated modern anxiety.

The films’ writer, James Wong, said that:

“By placing the premise of the film on the inevitability of death, we play a certain philosophical note.”

What occurred to me when rewatching the franchise is that dying itself is not the source of the horror. It is the nature of the deaths; undignified, meaningless accidents that destroy all illusions of control.

When characters are struck down in FD, to both the audience and the other characters, they are transformed into objects — not just by being reduced to a mush of blood and bone on the sidewalk, but also as objectified, morbid curiosities, stripped of their former character and autonomy.

It could be argued this isn’t unique to FD, that grisly murders is the essential component in all slashers. But these aren’t murders, there is no killer. In other slashers, the antagonist is a demon, a sociopathic doll, a serial killer: a figure of absolute evil. Compared to this evil, character deaths can have a semblance of meaning — the victims assume a certain virtue and dignity.

But there is no absolute evil in Final Destination, giving these ‘accidental’ deaths a queasy sense of ambiguity. When there is no instigator but the natural workings of death, who do we blame? How do we avoid it? FD hints at a terrifying possibility: that of the meaningless death, where nobody is to blame, nothing is learned, and no meaning can be eked out.

It would be easy to cite 9/11, the war on terror and the ambient atmosphere of fear following as influences on the franchise’s obsession with death spectacle. But these cultural developments occurred after the release of the first film — and they still left room for heroes and villains, motives, noble sacrifices, meaning.

Really, the basis for FD’s horror is the lack of narrative devices in the modern world to comprehend fatal accidents — and death more broadly. With the decline of religious faith in the West, there are fewer frameworks to make sense of these traumas. You can complain about the safety procedures, campaign for public awareness of the dangers of runaway shopping carts, but easy consolations won’t fill the empty space left behind.

The freak accident robs individuals of autonomy, and moulds their public legacy into a humiliating symbol of the tragedy. Poor Sandra will always be associated with the lethal potential of sunbeds; was she always so vain? Death peels back the thin veneer of control to expose our ultimate helplessness.

Without an omnibenevolent God looking out for us, we’re left with two options. We can live with a deep, ingrained comprehension of our own mortality, our lack of ultimate control over existence. This requires disengagement from the ego, a lifetime of conscious effort to avoid hiding behind comforting illusions — terrifying freedom.

Or, we can parse together a fragile notion of control from the multitudes of systems surrounding us in the modern world. From the mundane consistency of bus schedules, regulated construction work, accessible healthcare, to the more abstract chains of power, these enmeshed systems appear infinite in scope. Infinite stabilisers, protecting us from chaos.

Viewed together, the systems help generate an implicit assumption of underlying order beneath the world. Order that places us as free agents within a universe serving our interests, existing to bolster our needs and wants. There may be instances of horrific violence in the world, but these are blips from the norm, and they don’t happen to us.

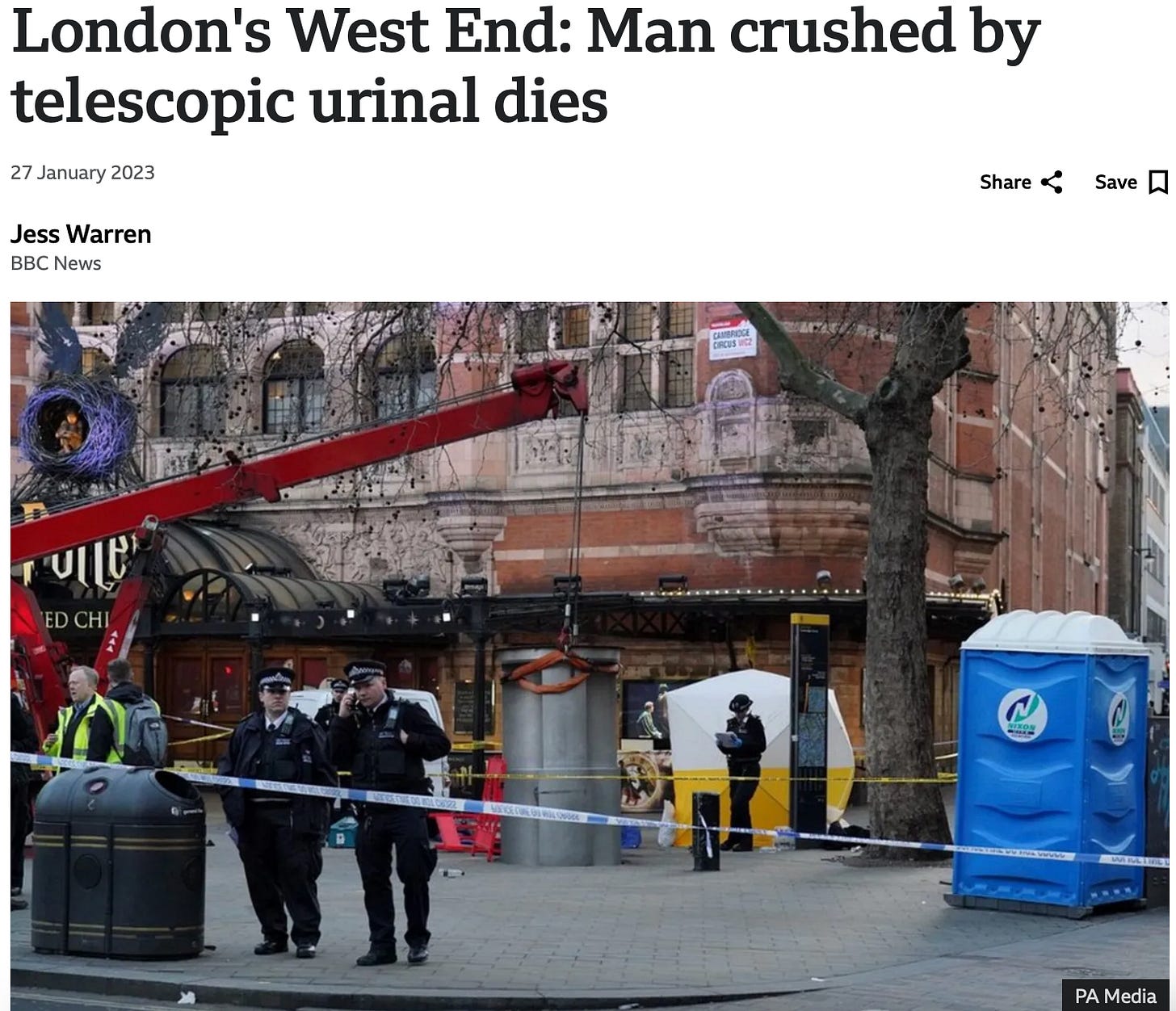

FD reverses these assumptions. Surgeries go awry and snip the brain stem. Cranes destroy instead of build. Buses run red lights and annihilate the flesh. The safety net of systems protecting us from the dangers and inconveniences of being human are suddenly turned against us, and our belief in control. There is a grand order of being, but it does not operate for our benefit.

Confronting the fragility of our existence can be paralysing. Final Destination doesn’t posit any of these ideas directly, merely hinting towards them, but it still provokes a profound sense of unease in the viewer.

A close relative of Final Destination is local TV News. Both serve up pre-packaged death spectacle as a form of entertainment, feeding on audiences’ morbid curiosity. In the case of TV News, death is uniformly tragic, but this uniform is constricting. Individuals are trapped as symbols of tragedy, and the audiences’ possible responses are limited to stock feelings: ‘Oh dear’, ‘The poor family’, ‘What a terrible way to go’.

There is another, equally natural reaction to FD’s death sequences, unacceptable when watching TV news: the stifled laugh. The final plunge of the knife is a release of tension that draws an emotional response out from the viewer, be it shock or giggles. And when the characters are fictional, there is no need to hide your morbid fascination with gratuitous violence, no need to suppress how entertaining it all is.

Maybe this is too harsh. All dread and no levity is exhausting, and unsustainable. Dark humour, the opportunity to laugh at the sheer absurdity of the violence, is a necessary part of the FD formula. Final Destination (2000) manages to tread the fine line between dark humour and grim self-seriousness in a manner that entertains without compromising atmosphere.

But perhaps inevitably, from Final Destination 2 (2003) onwards, the franchise began to devolve into a crueller, more voyeuristic fare. The uneasy balancing act of atmosphere and humour toppled over — death sequences are mined for maximum spectacle, engineered solely to subvert audience expectations and elicit a reaction.

The ensemble hollowed out into crude caricatures of the era: the nerd/pervert, the stoner, the slut, the black guy, etc, and the plotlines became thinner and thinner — really just filler space between those money-shot death sequences.

This culminated in The Final Destination (2009). The film was made just over fifteen years ago, but is one of the most dated, nasty artefacts of the 2000s. Characters are credited as MILF, Racist, Racist’s wife, MILF’s husband. Brown 3D sludge effects are soundtracked to Nu-metal grot. It is 80 minutes long with a $40 million budget2. There is some sadistic glee to be had in watching horrible people wade through a universe out to kill them, but it’s tediously one-note, and leaves a bad odour.

Without any substance attached to the characters — no reason to care — there is no deeper sense of horror beyond the empty thrills of the death sequences. They are crafty studies in tension-release that entertain, but they don’t linger.

These misgivings come from a place of love. Even at its most disposable, the Final Destination series depicts the stark absurdity of death in a way that buries into your psyche. And at its most effective, it makes you reflect on the illusions of stability and control we rely on in the modern world; the thin line between life and the mushy pile of spectacle on the roadside.

Expanded from ‘On Final Destination’ in Gleaning Issue #3.

The FD franchise understood as the original five films (2000-2011). Maybe in a later post I’ll look at how Bloodlines (2025) explores these themes.

If you ever watch it consider the $500,000 that goes into every minute.